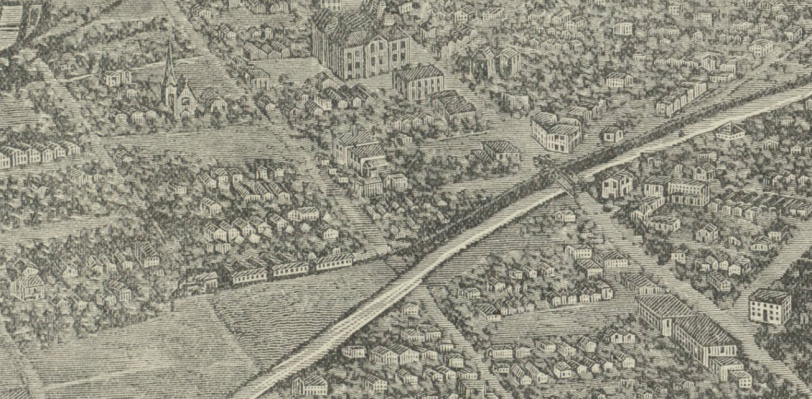

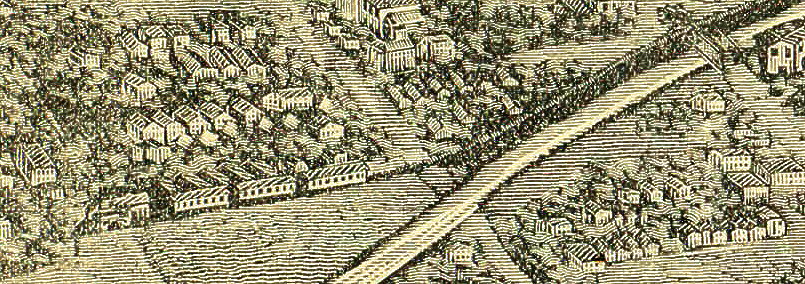

Bird’s-eye view of Denver, 1887. Created by Rocky Mountain News. Courtesy DPL Western History Collection CG4314.D4 1887.R62

” AN EPOCH IN THE HISTORY OF DENVER. The Circle Railway, when completed, will be twenty miles in length, completely surrounding the city with it’s track and stations, and will be the means by which the now cooped-up inhabitants of the city can reach suburban homes at a trifling expense and with a rapidity that will ROB DISTANCE OF ITS TERRORS.” (Rocky Mountain News, 1/28/1882).

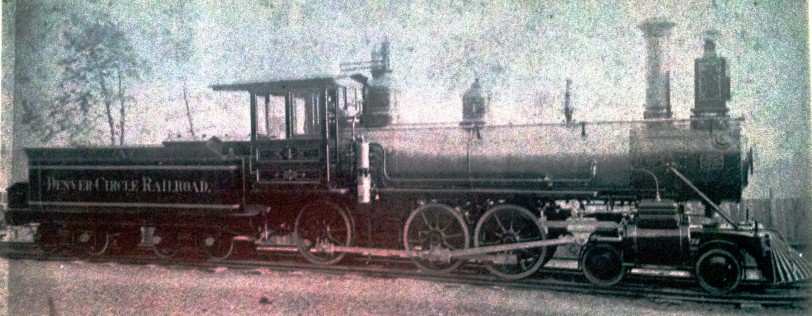

Denver Circle Steam Engine #4. Photo taken by the New York Locomotive Works before delivery to Denver.

Rail Rules Denver

Denver and La Alma Lincoln Park really started filling in the map when the railroads arrived in 1870. The struggling settlement aspired to offer all the conveniences of civilization, and after dependence on horse and wagon, the speed and reach of rail was the “internet” of it’s day. The railroad revolution dominated Denver for decades to follow and delivered the industry and commerce credited with the city’s survival and success. We grew exponentially in the next thirty years, and Lincoln Park was largely built by the Denver and Rio Grande. The introduction of the Denver Circle was considered a great step of progress, and the tale of it’s place in Denver history deserves resurrection. While the railroad never achieved the planned route around Denver, it certainly pushed the limits of the the city to the south. Along the way, the Circle RR would also become associated with one of Denver’s most infamous nights of debauchery. Closer to home, residents of Inca Street frequently battled the tracks that ran down the center of their narrow residential road. Sabotage and lawsuits with neighbors were among the many difficulties the Circle encountered before its demise.

From the Center of the Circle

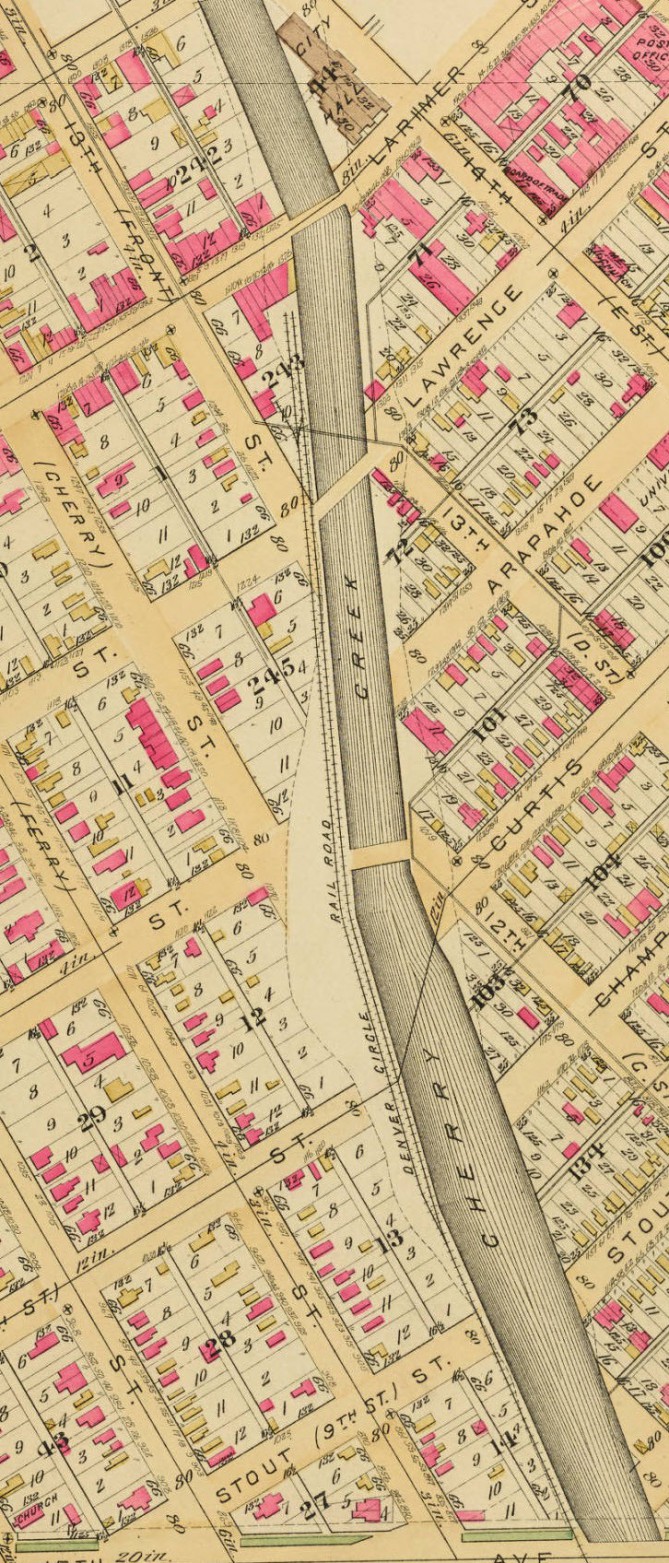

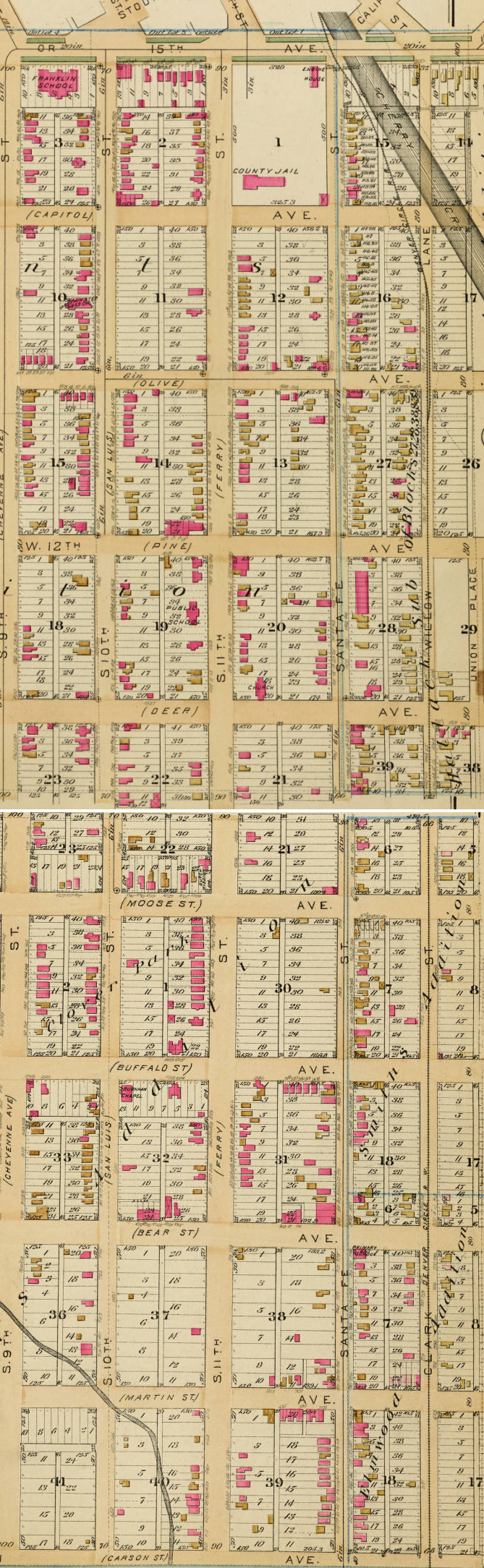

So many years after the streetcars were removed to accommodate our cars, most of us have no memory of that lost landscape. At the time the Circle RR was conceived, homes were built as far out as a horsecar could take you. If we remember that the Cherry Creek bed ran a different and wider course in the early years, we can imagine the path it took through La Alma Lincoln Park. It started across the creek from downtown, at Larimer Street. It’s trellised tracks ran along the bed, and veered onto Willow Lane and Clark Street (now Inca St) at Capitol Avenue (14th) Ave. It is remarkable to imagine that a train ran straight through today’s King Sooper’s, the state’s busiest grocery store, and continued south, a short block parallel to Santa Fe Drive all through the neighborhood! Stations were located at Colfax, Deer (11th), Bear (8th), and Carson (6th) before continuing out to the Mining Exposition, San Souci Gardens, or Jewell (Overland) Park.

Denver Circle from Larimer Station on Robinson Atlas 1887 Plate 2. Courtesy DPL Western History Collection C978.81 R562at 1887

Loveland’s Legacy

The idea to introduce a circular steam line came from William A. H. Loveland, and his Denver Circle Railroad was a unique endeavor in a couple ways: with steam powered engines, it would instantaneously expand the commutable distance for residential development and offer inter-city freight delivery with tracks that circled the city. Mr. Loveland had previously created the Colorado Central Railroad Co before losing control of it to the Union Pacific. And, fortunately for Denver, his political efforts to anoint Golden as the state capitol were unsuccessful. After losing a race for the governorship to Pitkin in 1877, he returned to the business of rail. A franchise was granted by the city in January 1881.

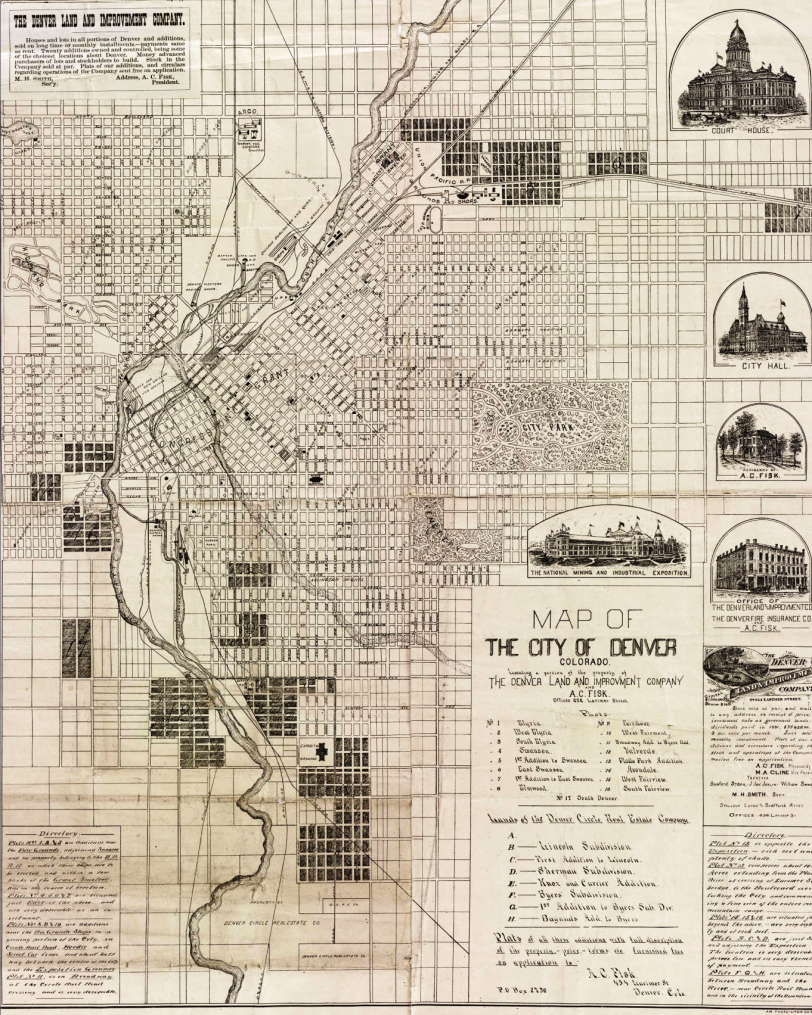

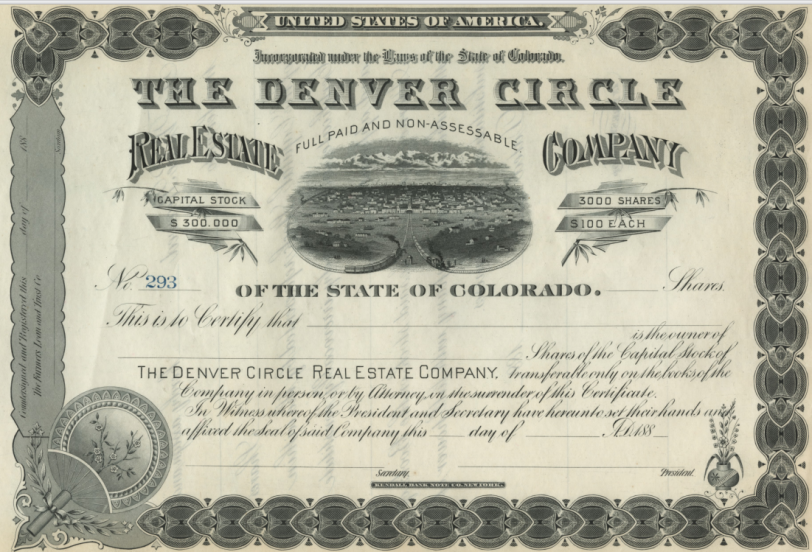

Like many of his contemporaries, Loveland’s plans for “improving” Denver were motivated by real estate development opportunity along it’s route. In conjunction with the railroad company, Loveland and his partners incorporated a construction company, the Denver Circle Railroad Real Estate Company, and The National Mining and Industrial Exposition. It is fair to suggest that the once largely vacant land from today’s West Wash Park southwest to Overland Park was first made viable for development by the Denver Circle line.

Only as Good as Where It Gets You

Just like today’s light rail expansion makes La Alma Lincoln Park’s 10th and Osage Station more valuable and useful, the Circle’s ridership needed places to go to get them on the train. The more destinations reached, the more ridership a train can expect to see. The larger route and properties served by the Circle can be seen on the map below, however since it is from 1882, it does not show the later extensions to DU or Clay Street. Clicking it gives you a zoomable image.

Map of the city of Denver 1882 Denver Circle Real Estate. Courtesy DPL Western History Collection CG4314.D4 1882.F5

Notable Destinations

Mining and Industry Exposition Fairgrounds

Located between Broadway, Logan, Virginia, and Exposition. The Queen City boosters constantly promoted its assets to help drive growth and development. The idea was that

“the Exposition should become permanently an annual event…open on August 1st and to close on September 30th. It was felt that the necessity existed for removing the many erroneous impressions prevalent, and showing that this part of the United States, instead of being in one portion a barren desert, and in another mass of snow clad mountains, really contains a soil encouraging to the agriculturist, and a marvelous diversity of native minerals…”

Loveland was on the board of directors with fellow railroad man, A C Hunt, and cooperation with the Denver and Rio Grande was needed in delivering the materials to build the breathtaking building.

![National Mining and Industrial Exposition building. The National Mining and Industrial Exposition opened August 1, 1882 at the corner of South Broadway and Exposition Avenue in Denver, Colorado, exhibiting mining and industrial equipment and resources. The buildings were removed after the third annual exhibition in October, 1884. Long, white tents and covered wagons stand in front of the complex near a railroad track. [1882?] Courtesy DPL Western History Collection C-94](https://lincolnparkhistory.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/national-mining-and-industrial-exposition-building.png?w=812&h=439)

National Mining and Industrial Exposition building. The National Mining and Industrial Exposition opened August 1, 1882 at the corner of South Broadway and Exposition Avenue in Denver, Colorado, exhibiting mining and industrial equipment and resources. The buildings were removed after the third annual exhibition in October, 1884. Long, white tents and covered wagons stand in front of the complex near a railroad track. [1882?] Courtesy DPL Western History Collection C-94

San Souci Gardens

Located between Logan, Sherman, Virginia and Dakota. Intended as a traditional beer garden, San Souci was the brainchild of Walter von Richtofen, Denver’s castle-loving German Baron. To boost poor attendance, the colorful nobleman decided to introduce a night for the “sporting element,” which was a euphemism for the underworld that included gamblers, pimps, and prostitutes. Denver had its fair share of this sort, and plenty more respectable but curious citizens were also in attendance. While mild to start, the night would become legendary for it’s bacchanalian, booze-fueled sex and brawling.

The ‘big night at Souci,’ from all reports, formed one of the striking bits of conversation around Denver for a long time after, but it was carried on quietly between the men, and that some of the pioneers say that if it had been held in some of these later days, there would have been a moral uprising of some people, for it was a shock, even forty years ago. ” (RMN, 17 July 1921).

Sans Souci concert gardens. Members of a band pose on a gazebo-like bandstand attached to a building at the concert gardens in San Souci Park in the Washington Park West neighborhood of Denver, Colorado. Men and women stand on the porch and on the ground nearby. The building features a high pitched roof, wrap-around porches, awnings, and small ornamental steeples. Courtesy DPL Western History Collection X-27716

Loveland and the Baron were suitably embarrassed by their new reputations as proprietors of sin, and such invitations were not extended again. Soon after, Loveland retired and sold his railroad interest to Charles A. Jewell.

Jewell (Overland) Park

Located on between Jewell, Florida, Santa Fe and Platte River. Started as a picnic area, it had a few different uses before becoming the municipal golf course we know today. In keeping with the Denver Circle’s clientele, the park was used for horse races, and later a hot rod track. It briefly served as a tourist campground before the Overland country club and golf course took over the site.

Exterior of Overland Club House, Denver. The clubhouse of Overland Park stands in the midground at the end of a dirt driveway in Denver, Colorado. First known as Jewell Park, Overland Park was started in 1883 by the owners of the Denver Circle Railroad. The park was intended to attract passengers to the company’s trains. Henry Wolcott assumed ownership of the park in the late 1890’s and changed its name to Overland Park.Courtesy DPL Western History Collection C-168

Sabotage, Vandalism, and Lawyers

While runaway trains and accidents occurred with other companies, the Circle had a difficult safety record. Derailments caused by water poured in freezing temperatures and piles of snow pushed onto the tracks along Inca Street were common, and some residents went as far as climbing aboard, slashing seats, busting lamps, and destroying passenger car interiors. The customer experience was suffering, and so were the company’s revenues. The Willow Lane case, heard by the Colorado Superior Court, set a pivotal precedent.

“The jury returned in half an hour with a verdict of $750 for the plaintiff. A large number of other suits of this nature have already begun, and several are on the tapis, the would-be litigants only awaiting the results of Bayer’s suit.” (RMN, 1882 June 28)

Payments the Denver Circle would be required to make to property owners along the the RR’s path further encumbered the enterprise.

The End of the Line

The initial track covered two and a half miles and despite expansions, the owners never really made the operation profitable. In 1886, the Denver and Santa Fe RR bought it in a foreclosure sale with the intention of using the right of way to access downtown. It pushed ahead with investments and settled all of the Circle’s debts. Then, finding citizen opposition to the heavier traffic and wider tracks, the city denied the franchise renewal under the new organization. The D and SF abandoned the tracks when it gained access to town through Governor Evans’ Denver Texas and Gulf lines. The tracks were eventually dismantled in fits and spurts over time; some salvaged, some simply buried.

The Denver Circle’s Larimer Station on the west bank of the Cherry Creek. Image is from the 1920’s, long after the Circle shut down.

In 1921, the Denver Circle story was resurrected in the Rocky Mountain News when Denver Gas and Electric employees were surprised to uncover some old tracks where they were digging at the intersection of Stout St and the Cherry Creek. Not surprisingly, the tale of the night at San Souci was most vividly recalled in describing the Circle’s legacy. Today, we can use this story help imagine an earlier landscape when rail ruled Denver, and trains and public transit fueled La Alma Lincoln Park’s residential development.

Sources

Robertson, Don & Cafky, Morris & Haley, E.J., Denver’s Street Railways, Vol 1 1871-1900, Sundance Publications, LTD. Denver, 1999

Davis, Elmer O., “The Denver Circle,” Engineers Bulletin v42 #6 June 1958 p12

Smiley, Jerome C., History of Denver, The Denver Times/ The Times-Sun Publishing Co., Denver (Colo.) 1901

“From a Race Track to a Golf Course” Denver Municipal Facts, January-February, 1931, p4

“Damaged Lots” Rocky Mountain News, 1882 JUNE 28, p1 c3

“Rails Recall Wildest Nights” Rocky Mountain News, 1921 JULY 17, Feature Section

“A Round Railroad” Rocky Mountain News, 1882 JAN 18, p 8 c2

“Superior Court” Rocky Mountain News 1884 OCT 31, p6 c2

Bird’s-eye view of Denver, 1887. Created by Rocky Mountain News. Courtesy DPL Western History Collection CG4314.D4 1887.R62

Pingback: “The only wagon road running southward entered Denver by way of Ferry St…” | Across the Creek

Pingback: Broadway Park: The Denver Bears’ First Home in La Alma Lincoln Park | Across the Creek